Some Places I Went To

It’s summertime! Don’t you just feel like going outside, exploring, spending time with friends, jumping into lakes?

Well, that’s more or less why there’s been nothing new here for two months. In years past I had a desk job for which I would get up every morning, in every season, and sit at a computer tip-tapping away. My back faced a window. Every once in a while I had to turn around and look outside. Something compelled me, even though there was nothing out there but a busy industrial road, a stone retaining wall, and a few trees grudgingly planted in the parking lot. And sunlight, and the sky, and those are what I was looking for. During coffee breaks or after lunch I would walk out to visit with them. The spacefaring frontier outlaws of Firefly are represented by a song that goes:

- Take my love, take my land,

- Take me where I cannot stand,

- I don’t care, I’m still free,

- You can’t take the sky from me.

It played through my head those days when I felt most unmoored from reality and went out to seek direction and speculate about what the clouds were telling me. But even with their help, I still sank into a sort of stupefaction, in which a day howsoever beautiful was nearly powerless to lead me outside. I was in the city. Where’s the outside? Yes, there is outside there. But for me, trying to spend quality time with it was an exercise in tantalism.

Now that I’ve divorced myself from the city I find myself interested more in doing stuff, being with people, going on walks, and less in planting myself in front of a screen. Though I should make sure to disclose that I have a good old self-defeating pattern in which I want to do some writing, but I don’t want to be at a screen to do it, or even sit still or exert effort, but the sense of obligation lingers, so instead I sit at the computer and feel so demoralized that instead of buckling down and being creative I just do mostly-pointless research and look at funny pictures, and so I end up spending probably a lot more screen time than I would if I just plowed through the discomfort and wrote. Here I am now, enjoying writing. It only took half a week of dinking around to get here.

In any case, now where’d I leave off?

The Rest of the Trip

There was this bike trip I was taking.

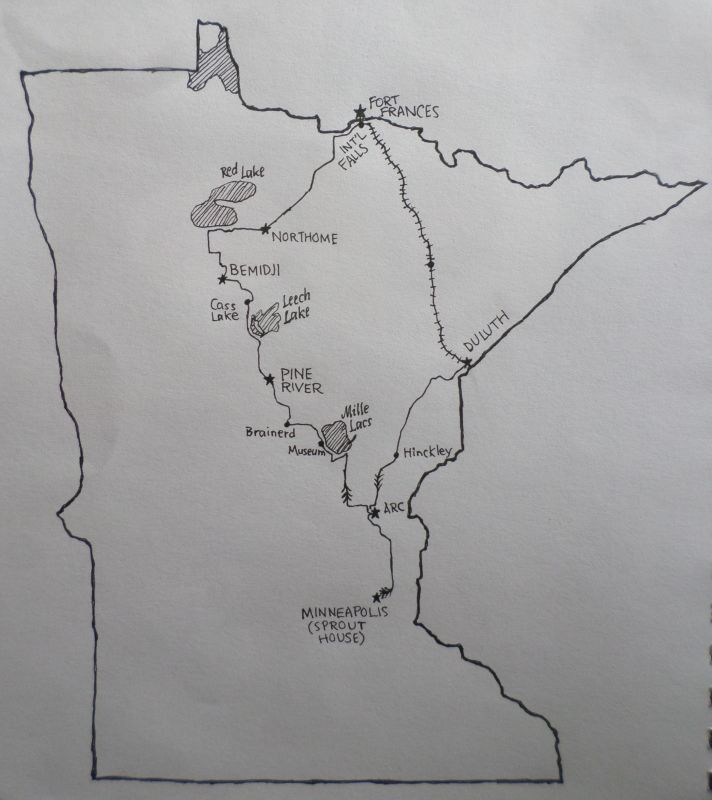

Last time I wrote, I’d just gotten to Bemidji. That was more or less the halfway point of the trip, timewise. Even though I’ve ostensibly written about the first half, all you know about it is that I worked at a farm and wrote some haiku and it rained at least once. Be that as it may, I believe I’m still going to leave the first half to cover another time, mainly because of Pine River, which at some point will probably be figuring prominently in a whole other post. Right now I’m going to tell about what I did in Bemidji and afterwards.

Bemidji

I came into Bemidji on a rainy Saturday afternoon and was drawn, much like a moth, to the prospect of light and warmth, in my case in a coffee shop that looks out over the length of Lake Bemidji. I’d given up coffee a week or two prior, but coffee shops still have a gravitational pull on me. There’s always tea. Inside I found a computer, free to use, and made use of this rare amenity to post my haiku. When the place closed I was like Jell-O removed from a pan, and hustled up the lake to make a damp camp. I figured I’d get to know the town tomorrow. But as it turned out, everything in Bemidji is closed Sundays, and instead of actually making effort to meet anyone, I wasted the day good and proper with the coffee shop computer and a book.

The next day I planned to ride on northward, but as I struck camp I stopped short. I had shortchanged Bemidji, I realized, and myself. I couldn’t go on yet.

So I rode back around Lake Bemidji (Bemijigamaag: Where the Waters Cross) to a bait shop I’d noticed, where I got some leeches and some advice, the latter leading me to a little fishing pier right there downtown, where the young Mississippi River enters the lake for a short visit before carrying on toward the Twin Cities, the Quad Cities, St Louis, Memphis, and the Gulf of Mexico. Here a kid could skip a stone across the Mighty Mississippi. You’d never know that it picks up enough help later on to swell to three miles across. The pier is a couple dozen yards downstream from one of the first highway bridges on the river, lightly graffitied. It seemed somehow that in the first city on the Mississippi, the first bridge should have more of a legendary quality. Aside from some more-or-less tasteful pillars faced in local round river rocks, it could’ve been a bridge anywhere, over any anonymous Minnesota stream.

When I arrived there was just one guy fishing. He was doing the kind of fishing where you don’t actually plan to catch anything because it’s the wrong time of day. If I wanted a walleye I could come back in the evening, he told me. Well I didn’t particularly care, so I joined him. After a while an eleven-year-old kid named Lakota, flush with school’s-just-out elation, showed up, as part of his plan to fish every day of summer vacation. He was excited to teach me everything he knew about fishing. And I was grateful for the help, since practically all the fishing I’d ever done so far had been in Crowduck Lake from a boat, and I hadn’t the foggiest idea how to fish from land in Minnesota. I was even grateful when he taught me things I already knew. The kid had initiative. I caught a five-inch perch, and counted the day successful. Anything else would just be gravy.

I left to wander around aimlessly, hang out some more at the coffee shop. When I came back in the evening a crowd had gathered, Lakota plus another eight or so guys casting off of every available railing of the pier. I posted up at an unlikely spot and proceeded to happily catch nothing. Eventually someone left a good spot and I took it. After a long time I caught a walleye. I talked with the guys. I’d been full of a feeling of aloneness, but it started to leave me. The guy next to me was Turtle Mountain Ojibwe and lived near the Red Lake Reservation to the north, and told me about it a little. The kids he was with were goofy and distractable. Lakota borrowed leeches from me. I enjoyed my night.

Red Lake

I pressed on the next day, now with a clear conscience, up due north to Red Lake and then east. While I was northbound and had a tailwind I was enjoying everything; had a lot of peace and goodwill, and maybe even some moments of full awareness of the world, sky suddenly a much deeper blue once I stopped humming the distracting song stuck in my head, trees alive in a way they weren’t before. In Ojibwe the word for “listen”, bizindan, is full of the word for “quietly”, bizaan. I quieted myself down so I could listen. Bizaan-ayaan. A woman at the coffee shop had warned me away from Red Lake. “I have a lot of friends there and I can tell you, they don’t appreciate white people coming through and just treating it like it’s their land.” Well, I offered tobacco as I came in and made sure to keep my spirit deferential, whether or not anyone could tell from in their cars. I can’t say if everyone was happy to see me rolling down the potholes and hills of Minnesota 1 along the southern shore of Red Lake, but I can say that it was on the rez, and only on the rez, that two people stopped their cars to have a chat with me about what I was up to. Both had passengers who got into it too, and it was smiles all around. The first was a lady who’d seen me in the morning outside Bemidji. “How’d you get here so fast?” The second just curious where I was going while I was stopped to read a sign (Endazhi-ganawendamang Nibi, “Where We Care for Water”). Both times we stopped to chat awhile, and everyone wished me good luck. If that’s a rough welcome, I’ll take it any day over getting completely ignored like I was basically everywhere else on the trip.

On the reservation I saw hand-stenciled signs for tribal election candidates, signs to encourage people not to do drugs, signs about the bygone ogimaaban1 who decreed the rez should be dry, a tribal college and government center sheltering under two giant eagles sculpted onto their roofs. But even where there weren’t signs I felt like I was somewhere, somewhere cared for. When I crossed the boundary back into Anglo Country, I felt suddenly betrayed; it was fields and tractors and pillaging, and I realized I hadn’t seen any of that for twenty miles. Hi, cattle. Now I was in land left behind,2 forfeit, no one’s using this so I’ll go ahead and ugly it up with a lot of mowing and machining. It was a hard return.

This bridge showed the seven original clan animals in the railings. Here, sturgeon, name.

Northome

The miles to Northome were long, stretched by a headwind. At 6:30 I made it, though now full of yawns. A sixteen-year-old working at the gas station gave me directions to a campground by a little lake. The day was ending, and the sunset there was a world of glowing, a Reminder. A crane flew across it and landed ten feet from my tent. A flight of geese threaded across the sky and disappeared. The kid from the station brought down a water bottle I’d forgotten there and I asked him how he liked this place. “I love it. I’ll be here my whole life,” he said.

When the last of the sun went below the horizon and left only its dim echoes of light bouncing off the thin sky, a switch was flipped somewhere and trapdoors opened, releasing a dense black cloud of mosquitoes, pent up all day and itching for blood. One minute I was sitting transfixed by the sunset, and the next I was diving for cover into my tent. I had the door unzipped for all of seven seconds and still had to spend the next hour swatting all the mosquitoes that had followed me in. The rest struck up a frustrated whine from where they blanketed the tent wall, and had I not staked the tent down they may have carried it away.

Just after I entered Red Cliff an old guy had talked with me a little at the gas station where I’d stopped for a breather. He mentioned that rain was expected. Hard to believe from that sunset, but I put up the rain fly anyhow. Well, if I ever learned anything true from a Native American elder, that was it. It rained and the wind came ripping through. The tent developed an alarming lean. Water seeped in. But for the most part, I stayed dry.

International Falls & Fort Frances

US Route 71 runs straight northeast from Northome to International Falls through bright green low country, lined with little yellow and white flowers. I sometimes went ten minutes without seeing a car. All alongside me were bogs, popple forests, regrowing clearcuts. Next to the highway there ran a little drainage, which I discovered beavers had dammed—so I went high-stepping down into the grass for a look. The water was such a clear brown—I hadn’t realized it could be both at once. Everything so alive. I was amazed how deep the matted grass from previous years went. I felt like a cat in a room full of pillows. Later I stopped at a big stack of logs and climbed up it. I stopped here and three all day, letting my curiosity direct. Biking is good for views but to actually get to know a place I still have to dismount and go walk and touch things. My body requires variety.

After Pelland, things took a turn for the worse. Lawns! Everywhere! They were massive, sprawling, unconscionable! Where did my woods go? Where are the red-winged blackbirds? Then the big box stores set in, and then the concrete, and here we are in International Falls. I ate, found a camping spot in a vacant lot I’d camped in the previous year, and slept, trying not to let it get to me too badly.

The next day I stashed my stuff in some brush and biked to the border. I only had one goal for the day: get some Canadian postcards. When I found them at an all-and-sundry store in downtown Fort Frances, they were at least ’70s vintage, the kind of postcards old enough that the printing company touted its ability to print in color. But having thus achieved what I set out for, I felt reluctant to just leave the country again. Fort Frances has narrow streets with pedestrians milling about, lined with old-fashioned storefronts. It bustles, in its modest way; it looks lived-in. International Falls seemed like a drab gray prospect.

I found a coffee shop in Fort Frances. I ordered a London fog and talked with the proprietor, a caffeine-powered individual named Ben. I told him Fort Frances seemed so much nicer to me than its counterpart across the stinkybridge. (Those of you who haven’t been there will be interested to learn that the two towns share a paper mill that stretches across the Rainy River; huge pipes full of wood chips or pulp or something run down the center of the narrow bridge that cars pass, and the whole town, in certain winds, smells like pulp, with an epicenter at the bridge.) “That’s funny,” he said, “it seems like just the other way around to me.”3 Maybe the grass is always greener, but I humbly believe I’m right. He told me International Falls seems to be paved much better. I suppose that’s true, but the thing is the whole town is covered in that pavement, vast stretches of it for no reason. When you’re in the northwoods, where trees take over any bare ground with stunning vigor, it seems like there’s no reason not to have some green in your town, but the folks there have chosen to hollow out a little island of dinginess in the sea of lively green around them, and now they’re living inside that decision, their unfinished basement of a town.

Ben gave me the scoop on Ontarian and Canadian politics, like how Justin Trudeau seemed great but turned out to be nearly as bad as all the rest. I learned from him that pot is becoming legal nationwide there this October. I suppose Vancouver’s skunk funk will become even more fragrant. And I wrote postcards. And eventually I crossed back over into the US, which here looked suspiciously Soviet.

The CN to Duluth

In the evening it was time to check out the switchyard.

I had decided to save a little time on my return trip by, if I could, catching a freight from I-Falls to Duluth. In fact I prepared for this possibility before I even left Minneapolis. Part of my gear was an old hiking backpack frame, across which I had strung a couple cables. The cables were for hanging my bike panniers; then I’d tie everything else on, and bungee the whole mess together, giving me a way to carry everything on my back and then heave it onto a train car in one go (and then the bike in a second go), rather than fiddling with clips and bungees and tossing bags on individually while the train airs up and leaves without me.

The International Falls switchyard is actually a few miles east of town in a place called Ranier. I crossed above the tracks on an under-construction highway bridge and then rolled the bike back through the dormant ground-level part of the construction, following along the highway, through boglike squish, until I got to the tracks where they go under the bridge.

There were three tracks, and each one had a train on it. Trouble was, I couldn’t see the head-end of any of them, even standing on the overpass—to the north the tracks went around a bend, and to the south the trains stretched so far I couldn’t make anything out at the far ends. So I would have to let all three of these leave, and wait until a train came that I would positively know to be southbound, on account of its coming in pointed south. In some circumstances I might’ve taken a chance or gone scouting, but today I didn’t really feel like explaining my travel plans to the border patrol.

Around 9:00 a southbound came in, an intermodal,4 on the track closest to me, and pulled to a stop. Time to strike. I carried the bike over it and walked along in the narrow corridor between it and the train on the second track, putting my target train between me and the bull run,5 searching out a car I could hide on. Walking between two trains makes me feel like a small animal. When you walk around automobiles you have a sense that they’re built to your scale. When you’re between two trains you become very aware that you can barely see over the wheels. I got all the way to the end of the train without finding anything better than semi-bad prospects, and turned around toward the head-end. After a while I settled for an okayish car with a very shallow mini-well.6

I lay the bike flat on one side, and my stuff and me flat on the other side (sleeping pad under me to keep something between me and the cold steel), and waited.

It was a weird train. Around 10:00 it started moving—but not very far. The sky darkened, the stars came out. It moved again, this time into the first floodlights of the yard. From that point on it would move forward a hundred yards or so, then stop dead for ten or twenty minutes, then repeat the drill. Meanwhile, I got treated to a tour of lots of different floodlit spots along the course of the switchyard. Sometimes I would dare to crane my neck up for a few seconds to see where I was. Still next to the bull run, was the answer, still in the lights. No one seemed to be paying much attention to my train, but one small slip-up can ruin a trip and a day very effectively, and I stayed hunkered down, in a constant heart-pounding fight-or-flight state. Yard workers walked around just one track away, blocked from seeing me only by a train that they could choose to climb over anytime. The train moved forward again. An engine was on the next track over, only two or three carlengths back, and its various mechanisms powered up and down automatically but nervewrackingly, continually making me wonder if a conductor was getting on board. I lay very flat. Sleep was out of the question. The train moved forward; more floodlights. This yard was endless. Every time I figured we were finally pulling out onto the road I landed in more floodlights.

Just to give the whole thing a good climax, when my train finally did get moving, so did another train right next to it, and I had to jump out of my sleeping bag in my long johns and hang onto the far side of my car’s shipping container in order to keep out of view of the other train’s conductor, my butt sticking out over the bull run where I prayed a car wouldn’t appear, while the two trains jockeyed back and forth a time or two. Mine came out ahead and the other one stayed in the yard, as I deduced when we got onto singletrack, where I could finally breathe and my heart could calm down.

For a while I couldn’t sleep because I was too excited. Eventually I settled down and consoled myself with the knowledge that I could watch these woods go by in the day too. But by 5:00 or so I was up again, packing up my stuff to a less visible configuration while the train crept by a siding, which luckily turned out not to have a passing train on it. Now woken up but good, I hung out the rest of the morning watching and marveling. Pristine, all of it! Most train tracks have had a highway built alongside them, crammed with buttinski motorists who would love to report any unapproved thrill-seeking to the authorities, which means you have to keep hidden for most of your ride. These tracks, at least starting from where I woke up (near Cook or Orr), barely get near a highway. What they do go near is peaceful tannin-brown creeks through lush bogs, thick bristling northland forests, and the occasional little town like Melrude or Shaw where there has never been a paved road. This was a rare ride. I paid close attention to appreciating it: the mist rising off a river rarely seen by any humans besides train conductors; a bog at dawn, chilly and like it was just thought into existence. I got deeply and viscerally cold in the humid dawn chill, but I didn’t mind; I just jumped up and down like a lunatic to keep the blood flowing, and smiled maniacally.

As the sun was starting to clear the treetops, the train stopped, for the first time since it’d left, under a highway bridge. I’d seen enough town name signs to figure I was close to Duluth. And I made a snap decision: since I had a bicycle, I would skip the whole fun drama of pulling into the yard while staying out of sight, then dodging around over and between strings7 to find a low-profile way out to the world. I could just bike into town. The beauty of the combination of bike and train impressed itself on me. This is something I could get used to.

Southerly

I plummeted (breaking the speed limit) down Route 53 into Duluth, which was a tangled confusion and a bigger city than I’d been in for a month. It freaked me out, but it wasn’t too long before I got safely out the other side of it onto the Willard Munger Trail, a bike path artfully punched through Canadian Shield granite and draped across the crashing of the St Louis River’s waterfall. In the early evening I found a clearing off the side of the trail and set up my tent, and before the sun was down I was.

The St Louis River crashes down below the Willard Munger trail bridge.

The Munger Trail took me as far as Hinckley and then left me to get to ARC of my own devices. I brought Misty one of Tobie’s world-famous cinnamon rolls, a Hinckley compulsory, and we talked about ARC’s mass exodus. Seems while I was gone, everyone living there decided that, for one reason or another, they had to leave. Only one person would be left (Medora, the one I gave the fern tattoo to). Misty, for their part, was heading to the Cities to start a job doing exterior house painting.

So we talked, and did ARC chores. Something we didn’t do is go to Feral. Misty was worried that the job wouldn’t be there for them if they took off to Colorado, and they needed to start making money ASAP, so they backed out, calling me to tell me the day before I got to ARC. That would’ve been of little consequence except that Misty was the one with the car, so that meant Willow and I couldn’t go either. Strangely enough, though, I took this pretty much in stride. Somehow I’d had a vague presentiment for months that, for some reason or another, Feral wasn’t going to happen, so I’d long since stopped being attached to the idea. The only thing was, they canceled two days before we were supposed to leave. Which left me with no plans for the upcoming week.

Turned out that, after staying at ARC for a few days and helping Misty move stuff, I pretty much just ended up going down to Minneapolis and staying there for a couple weeks: taking care of clerical things, moving some of my own stuff, having a breather, typing up a story I’ve been writing, meeting some interesting new people, going to a birthday party—you know, Minneapolis stuff. And that was it for the bike trip. No particular homecoming party or anything. I wouldn’t have really wanted one, except maybe one right when I finished if it had lots of food. I didn’t even bike back to Minneapolis; I caught a ride with Misty.

But you know what, I biked 600 miles. I just measured it with Google Maps, so I know. But while I was clicking from point to point on the map, anatomizing the trip, there were spots where I almost couldn’t bear to do it. I dragged the map and my Pine River campsite came into view. I marked it and then it seemed just so callous to drag the map on over to the next place. Like a betrayal of the week I spent there, drinking water straight from the river, writing, and dissolving and purifying myself into nature. Or how about that Little Free Library out in the middle of nowhere on the bike trail south of Cass Lake, where I stopped in the drizzle and left the copy of The Dharma Bums that I’d just finished? How about the little museum in Cass Lake where there was just one old lady running the whole place, but she turned on all the lights for me and let me dry off and look around at the incredible miscellany of the town’s history, and I forgot to sign the guestbook even though she reminded me five times? How about the Ush-Kab-Wan River, which I didn’t even get to breeze over because I saw it from the train and didn’t count any train miles, but which keeps calling to me to canoe its entire length someday, to experience its serenity? How about the old depot in Finlayson where after they renovated it birds still got back in and built a nest on a desk? (Of which pictures below, since I don’t know where else I’d ever put them.) I’m filled up with these moments now, hundreds of them; this bike trip was one of them strung after another, and it took me a month to gather them all into me, but I can’t sit here typing stories for a month, nor could you spare the time to read them, so I can only give you these little nibbles of what I found.

Crowduck

I gave myself two and a half days to hitch to Duluth before my Uncle Dan was scheduled to pick me up to take me to the annual family fishing vacation at Crowduck Lake in Manitoba. I got there in about three hours. So I had some spare time in Duluth. I found a camping spot in some trees by the dunes on Lake Superior, and during the days I wandered. I met a water protector down by the lift bridge. She explained that the water protectors are a lot of grandmothers, mostly Native, walking all across the continent, sometimes to important hearings or actions, sometimes just from river to river to river, always carrying a copper bottle of water, always praying for the water in the ground, in the rivers, in the sky, in our bodies. I thanked her for helping do it. For all the crowds city people can raise in protest marches, sometimes something quiet but full of determination and meaning is even bigger, like grandmothers who aren’t well-off to begin with or in their physical prime taking off to wander the country on foot for something they believe is more important than any of them.

After so long camping in river bottoms and by lakes and in the brush, walking around by day with just my feet to get me anywhere, when I got in Dan’s van with Cammy (8) and Cory (7) in the back and my Aunt Tracy in the way back, I had this strange period of having to arrive into another world: here people know me, I have history with them, I get around in a wheeled contraption that I didn’t have to flag down, I have a bed and shower waiting for me at the end of the day.

Stuff I did at Crowduck is mostly of interest to people who were there, and they don’t need to be told about it for the most part, because I already told them about it just after I did it. I’ve gotten better at poker, and earned about $10 over the course of the week, one nickel-dime-quarter pot at a time. It was the most prodigious blueberry year anyone can remember. They were popping out from every crevice, big fat round ones, full of flavor, and when I went out with Dan, Grandma, Cammy, and Cory, we picked so many Tracy was able to make blueberry buckle, twice. Four of us made the intrepid journey to Saddle, a rugged mile-and-a-fifth of hiking up granite escarpments and through boggy muck laid with logs meant to provide traction but which are also good at twisting ankles—including Grandma, who‘s 78 this year and was justifiably proud of the feat.

On the last night, I went out to look for northern lights, as I’d been doing every night of the week. There hadn’t been any on the other nights and there weren’t any tonight, but I did find the spirit of the lake. The water was black and perfectly still. Silence. I hushed up too.

All week I offered tobacco to the lake when I started fishing. Crowduck Lake is on Ojibwe land and it seems right to me to carry on Ojibwe traditions there. But each day it mostly felt predetermined, mechanical, a gesture not quite empty but in search of its contents. I hadn’t allowed myself to properly meet the lake. The day I arrived, I went and looked at it, but never saw more than its surface, because while I was imagining that I was trying to et the lake have its say, really what I was listening to was the hustle-bustle of the family, and my ideas of what I needed to do next. Which never left me all wek, and accordingly I never fully relaxed.

At the lake that last night there was no hustle left to bustle. Just silence and Crowduck Lake. I imagined it, now, as it is in the winter, and as it is under the surface, and as it is when I’m not viewing it as a stockhouse of fish. It is ancient, and it is cold, and it whirls with toothy life. But that’s not to say it’s hostile; it is all these things, and it just is them. I considered my status, my spirit’s presence as an occasional visitor. Suddenly I felt like I’d been very entitled all week. I asked and asked from the lake, but barely gave back anything; a pinch of tobacco once a day but only the barest sliver of my attention and deference, just the merest glimmer of a recognition that I was in the presence of a presence much older and wiser than myself. I was a bad friend. But I also felt that paying it this attention, on the silent last night, was an apology it accepted, in both of our anticipation of a better relationship in the future. I suddenly felt more curious, and interested to come to the lake next year not just for the family and the poker but to explore Crowduck, to go fishing where I feel called to fish each day, instead of somewhere I just default to because I have no ideas. To get to know the lake and its places, as I started to do on the last day, when I took my mom and caught a few fish in a cove that no one I know has ever fished before, a tiny place where a little creek empties into the lake. It seemed right that this year, when I finally ended up meeting Crowduck after coming here all my life, was also the year when I first noticed some cormorants, some crowducks, gaagaagiishibag, flying over North Bay.

Ashland & the Chequamegon Bay

Awesome storm clouds near Washburn.

Dan dropped me off south of Duluth where Route 2 leaves Route 53, and I hitched a patchouli-scented ride to Ashland, Wisconsin, where I arrived two days before anyone expected me. I was there to talk about the Lake Superior bike trip with the other people I’d be biking around it with, Katie and Maria.

The first night I had no idea what to do with myself, freshly plopped back into eternal stranger status after a week with family, arriving in a town I’d once spent maybe a couple hours in. I futzed around until 9:00, when I went out to scout out a camping spot. I found people lining the highway, carrying little American flags, as far up and down the road as I could see. “Is there some sort of parade?” I asked the closest person. He explained that an unknown soldier’s remains from Pearl Harbor had recently been DNA-tested, and they were now convoying the remains back (from the Minneapolis airport) to his home in Michigan. Kid was 19. Well, I stuck around, talking to the guy and some of his family, explaining what was up with my giant backpack, and waited for the convoy, which arrived in a cacophony of motorcycle rumbles during the later stages of dusk. As I was saying goodbye the guy pointed out that I could probably stay behind that garage over there, since tomorrow was Saturday and no one would be working there, unless things had changed since he’d retired eleven years prior. And so I had my first night’s stay by way of serendipity, and it was a great spot, too.

Since then I’ve discovered that Ashland and the Chequamegon8 Bay are full of small-town serendipity like that. The next day I hung out at the Black Cat, the coffee shop (another of those!), really the only coffee shop to speak of in town, but such a place it is, with shelves of good books for sale inside, which I looked at as I passed the time and wondered idly what I might do with myself for a few days. There I ran into Kitty, who I’d last seen when we were both living at The Draw over a year ago. She recognized me right off, and asked what the heck I was doing in town, and before I knew it her significant other Michael was there too and I was being invited back to their house until the bike trip meeting could be convoked.

That ended up being a longer-term proposition than any of us knew, because the other thing about Ashland, or at least the subsection of Ashland’s demographic I’ve been hanging around with, is that outside of some people’s jobs, schedules are an invention that’s never found a home here. I hung out for a week, reading books and hanging out in the house, relaxing for once, occasionally getting swept up into some adventure to a lake or something, before we got close. Then after a few more days I volunteered to go down to southern Wisconsin with Katie in her Mercury so she could catch a ride to a concert in Chicago and then bring back a Volkswagen she’d left elsewhere in Illinois. I spent a few days sleeping in the Mercury in Minneapolis and a couple days after I got back we managed to have the bike meeting.

And here I am still, because I kinda like it here. Sure, at the moment I’m a little at loose ends in the daytime while everyone’s at work and all I have to do is clean stuff (I’ve been asking around about temporary jobs, but failing those I’m probably going to bike to The Draw tomorrow and stay for a few days). But the bigger picture is that Ashland is a place full of people I get along with. People who want to go back to the land; people who’ve actually done it. It’s not just idle city dreaming. Michael and Kitty have been actively searching for land they can buy for over a year (and are going out on Wednesday to visit what might be The Place for them). I think there’s momentum here, impetus toward the kind of projects I want to be a part of, so I want to stay and help the dreams that abound here become realities. Moving here is a nebulous plan with a nebulous timeline, but right now at least I’m willing to believe I might’ve found a place I can call home.

-

Late chief (ogimaa, “chief, leader”; -ban, “deceased”.) ↩

-

Interesting, too, that Anglo Country should feel that way to me, since the Ojibwe word for “reservation”, ishkonigan, literally means “left over” or “put aside”. ↩

-

At least I think he was the one who said this to me. At any rate someone in Fort Frances did. ↩

-

Train carrying shipping containers. ↩

-

The gravel road along the tracks that railcops (“bulls”) and crew transport cars use. ↩

-

A little depression, outside the main load area, that’s part of the design of some intermodal cars—as contrasted to a regular well (much roomier), which is the space left over between the end of a shipping container and the wall of the well it’s put into, on intermodal cars that have a floor. ↩

-

Connected-up strings of train cars with no engine. ↩

-

shə·WAH·mi·gən—the only word I know with a silent q. It comes from Ojibwe Zhaagawaamikong “at the sandbar”, by way of French mushmouths. ↩

File under: Year of Listening, biking, trains, photos · Places: Minnesota, Canada, Chequamegon

Note: comments are temporarily disabled because Google’s spam-blocking software cannot withstand spammers’ resolve.

2 Comments

Dave

HistoryEpic adventure!

Mom

HistoryWhat amazing stuff!….mom